Information about our local monument

In the centre of Cranwell Village we have the Village Cross. This monument includes the village cross, a Grade II listed standing stone cross of medieval and later date. The cross, which stands in a paved area at the centre of a road junction south west of the parish church, is of stepped form with a shaft and cross-shaped head. The monument includes the base, consisting of three “modern steps” (c.1912) and a medieval socket-stone, the shaft, part of which is also medieval, and a modern cross-head. The cross was restored in 1912.

Cranwell village cross is a good example of a medieval standing cross with a quadrangular socket-stone and octagonal shaft. Situated at a road junction in the village centre, it is believed to stand in or near its original position. Limited development of the area immediately surrounding the cross indicates that archaeological deposits relating to the construction and use of the cross in this location are likely to survive intact. While the socket-stone and part of the shaft have survived from medieval times, the subsequent restoration of the steps, knop and head has resulted in the continued function of the cross as a public monument and amenity.

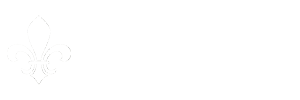

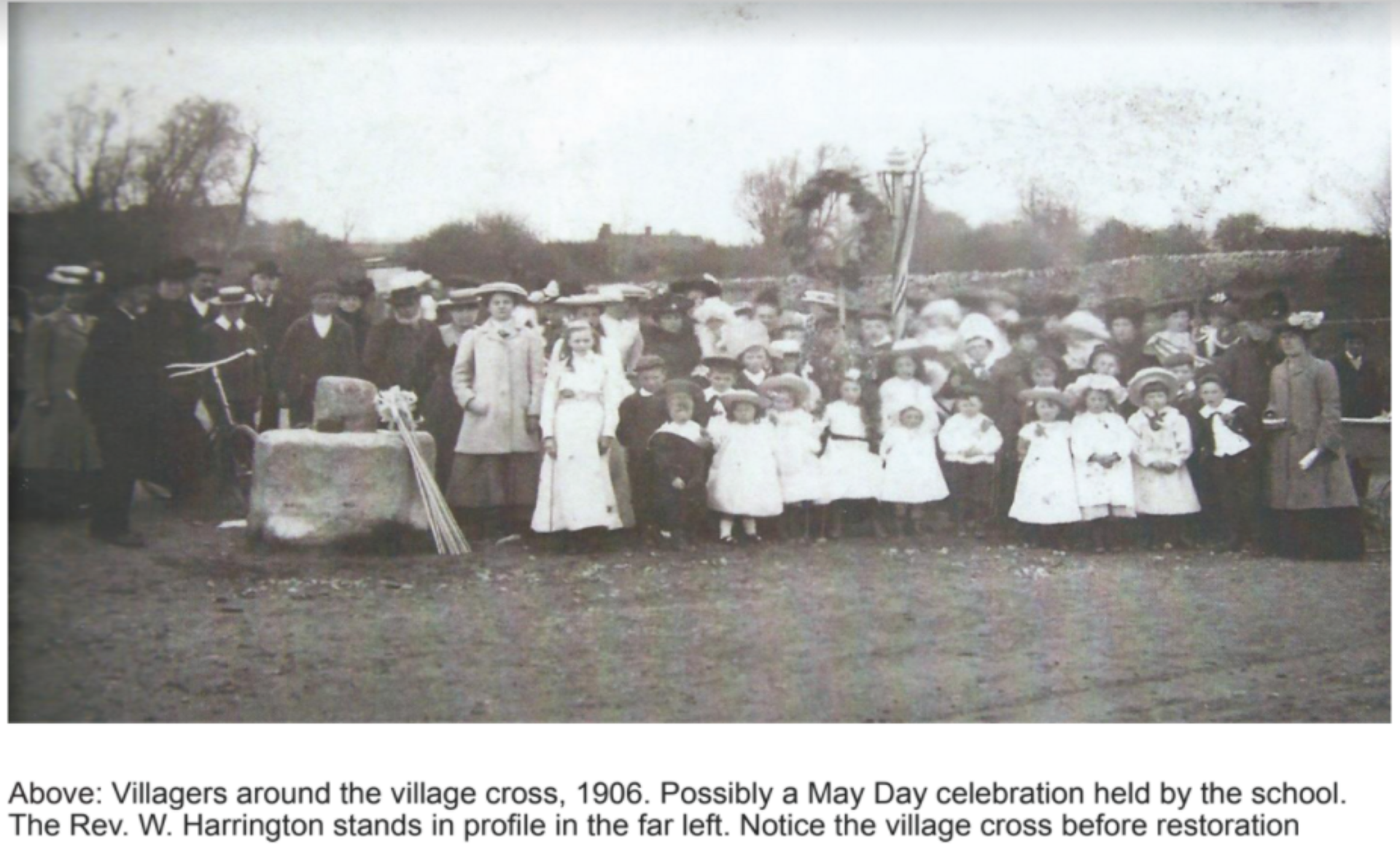

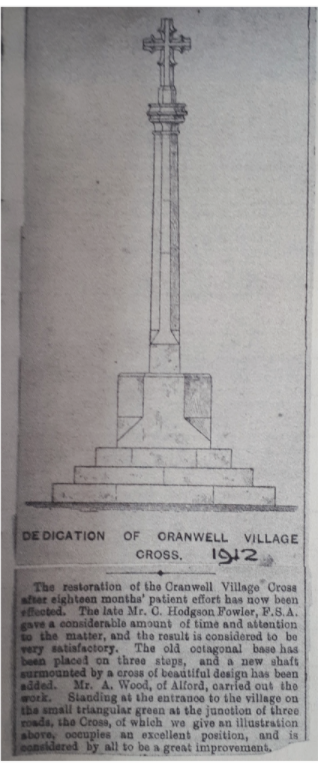

The village church was restored in 1903-04 and the restoration of the Cranwell village cross was completed in 1912 after eighteen months' patient effort. The late Mr. C. Hodgson Fowler, F.S.A, gave a considerable amount of his time and attention to the matter and the result was considered to be very satisfactory. The old octagonal base was placed on three steps, and a new shaft surmounted by a cross of beautiful design was added. Mr. A. Wood of Alford, carried out the work. Standing at the entrance of the village on the small triangular green at the junction of three roads, the Cross occupies an excellent position, and was considered by all to be a great improvement. The two photographs show the Village Cross in 1906 before restoration and in 1913 after completion. Note the pond on the village green and the village water pump in the background.

This cross is Listed Grade II. The paving immediately surrounding the cross is excluded from the scheduling although the ground beneath it is included.

The steps are square in plan and are constructed of limestone blocks around a concrete core, and cover an area approximately 2.22 sq.m. Set onto the top of this step is the socket-stone, a worn limestone block approximately 0.9m square and 0.7m high. Each corner is moulded and chamfered so that the top of the stone is roughly octagonal in section. The north western and north eastern corners include the remains of carved decoration. Set into the centre of the socket-stone is the shaft, 0.3m square in section at the base, which takes the form of a modern red sandstone block; this supports a block of limestone with chamfered corners and tapering octagonal section which represents the bottom of the original shaft. The upper parts of the shaft are composed of limestone and sandstone pieces dating from a 20th century restoration. Above the knop is an ornamented cross-shaped head, also of modern date. The full height of the cross is nearly 4m.

Some background information.

A standing cross is a free standing upright structure, usually of stone, mostly erected during the medieval period (mid 10th to mid 16th centuries AD). Standing crosses served a variety of functions. In churchyards they served as stations for outdoor processions, particularly in the observance of Palm Sunday. Elsewhere, standing crosses were used within settlements as places for preaching, public proclamation and penance, as well as defining rights of sanctuary. Standing crosses were also employed to mark boundaries between parishes, property, or settlements. A few crosses were erected to commemorate battles. Some crosses were linked to particular saints, whose support and protection their presence would have helped to invoke. Crosses in market places may have helped to validate transactions. After the Reformation, some crosses continued in use as foci for municipal or borough ceremonies, for example as places for official proclamations and announcements; some were the scenes of games or recreational activity. Standing crosses were distributed throughout England and are thought to have numbered in excess of 12,000. However, their survival since the Reformation has been variable, being much affected by local conditions, attitudes and religious sentiment. In particular, many cross-heads were destroyed by iconoclasts during the 16th and 17th centuries. Less than 2,000 medieval standing crosses, with or without cross-heads, are now thought to exist. The oldest and most basic form of standing cross is the monolith, a stone shaft often set directly in the ground without a base. The most common form is the stepped cross, in which the shaft is set in a socket stone and raised upon a flight of steps; this type of cross remained current from the 11th to 12th centuries until after the Reformation. Where the cross-head survives it may take a variety of forms, from a lantern-like structure to a crucifix; the more elaborate examples date from the 15th century. Much less common than stepped crosses are spire-shaped crosses, often composed of three or four receding stages with elaborate architectural decoration and/or sculptured figures; the most famous of these include the Eleanor crosses, erected by Edward I at the stopping places of the funeral cortege of his wife, who died in 1290. Also uncommon are the preaching crosses which were built in public places from the 13th century, typically in the cemeteries of religious communities and cathedrals, market places and wide thoroughfares; they include a stepped base, buttresses supporting a vaulted canopy, in turn carrying either a shaft and head or a pinnacled spire. Standing crosses contribute significantly to our understanding of medieval customs, both secular and religious, and to our knowledge of medieval parishes and settlement patterns. All crosses which survive as standing monuments, especially those which stand in or near their original location, are considered worthy of protection.

Newspaper article 1912

Website: Historic England / Cranwell Village Cross

Information provided by Historic England website and Matthew Bayly